Thursday, January 5, 2017

The primary cause of the U.S. public debt is insufficient tax revenues.

We’re still great, but here’s how national-debt policy was captured by Wall Street and went crazy. You can see exactly when it happened in this graph. You can even see the first President Bush predict it in the video clip below. And then take it back when he gets a new boss. Now Trump is under the Voodoo spell, and this time the country really is losing its greatness.

Monday, November 9, 2015

Causes of Income Inequality in the United States

There are many potential causes of income inequality in the United States. They include market factors, tax and transfer policies, and other causes.

Market Factors:

- Globalization - Low skilled American workers have been losing ground in the face of competition from low-wage workers in Asia and other "emerging" economies. While economists who have studied globalization agree imports have had an effect, the timing of import growth does not match the growth of income inequality.

- Superstar Hypothesis - Modern technologies of communication often turn competition into a tournament in which the winner is richly rewarded, while the runners-up get far less than in the past.

- Education - Income differences between the varying levels of educational attainment (usually measured by the highest degree of education an individual has completed) have increased.

- Skill-Biased Technological Change - The rapid pace of progress in information technology has increased the demand for the highly skilled and educated so that income distribution favored brains rather than brawn.

- Race and Gender Disparities - Income levels vary by gender and race with median income levels considerably below the national median for females compared to men with certain racial demographics. Despite considerable progress in pursuing gender and racial equality, some social scientists attribute these discrepancies in income partly to continued discrimination. In terms of race, Asian Americans are far more likely to be in the highest earning 5 percent than the rest of Americans. Studies have shown that African Americans are less likely to be hired than White Americans with the same qualifications.

- Incentives - In the context of concern over income inequality, a number of economists, such as former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, have talked about the importance of incentives: "... without the possibility of unequal outcomes tied to differences in effort and skill, the economic incentive for productive behavior would be eliminated, and our market-based economy ... would function far less effectively." Since abundant supply decreases market value, the possession of scarce skills considerably increases income.

- Stock Buybacks - Writing in the Harvard Business Review in September 2014, William Lazonick blamed record corporate stock buybacks for reduced investment in the economy and a corresponding impact on prosperity and income inequality. Between 2003 and 2012, the 449 companies in the S&P 500 used 54% of their earnings ($2.4 trillion) to buy back their own stock. An additional 37% was paid to stockholders as dividends. Together, these were 91% of profits. This left little for investment in productive capabilities or higher income for employees, shifting more income to capital rather than labor. He blamed executive compensation arrangements, which are heavily based on stock options, stock awards and bonuses for meeting earnings per share (EPS) targets (EPS increases as the number of outstanding shares decreases). Restrictions on buybacks were greatly eased in the early 1980s. He advocates changing these incentives to limit buybacks

Tax and Transfer Policies:

- Income Taxes - According to journalist Timothy Noah, "you can't really demonstrate that U.S. tax policy had a large impact on the three-decade income inequality trend one way or the other. The inequality trend for pre-tax income during this period was much more dramatic." Noah estimates tax changes account for 5% of the Great Divergence. But many – such as economist Paul Krugman – emphasize the effect of changes in taxation – such as the 2001 and 2003 Bush administration tax cuts which cut taxes far more for high-income households than those below – on increased income inequality. Part of the growth of income inequality under Republican administrations (described by Larry Bartels) has been attributed to tax policy. A study by Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez found that "large reductions in tax progressivity since the 1960s took place primarily during two periods: the Reagan presidency in the 1980s and the Bush administration in the early 2000s.

- Taxes on Capital - Taxes on income derived from capital (e.g., financial assets, property and businesses) primarily affect higher income groups, who own the vast majority of capital. For example, in 2010 approximately 81% of stocks were owned by the top 10% income group and 69% by the top 5%. Only about one-third of American households have stock holdings more than $7,000. Therefore, since higher-income taxpayers have a much higher share of their income represented by capital gains, lowering taxes on capital income and gains increases after-tax income inequality. Capital gains taxes were reduced around the time income inequality began to rise again around 1980 and several times thereafter. During 1978 under President Carter, the top capital gains tax rate was reduced from 49% to 28%. President Ronald Reagan's 1981 cut in the top rate on unearned income reduced the maximum capital gains rate to only 20% – its lowest level since the Hoover administration, as part of an overall economic growth strategy. The capital gains tax rate was also reduced by President Bill Clinton in 1997, from 28% to 20%. President George W. Bush reduced the tax rate on capital gains and qualifying dividends from 20% to 15%, less than half the 35% top rate on ordinary income. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) reported in August 1990 that: "Of the 8 studies reviewed, five, including the two CBO studies, found that cutting taxes on capital gains is not likely to increase savings, investment, or GNP much if at all." Some of the studies indicated the loss in revenue from lowering the tax rate may be offset by higher economic growth, others did not. Journalist Timothy Noah wrote in 2012 that: "Every one of these changes elevated the financial interests of business owners and stockholders above the well-being, financial or otherwise, or ordinary citizens." So overall, while cutting capital gains taxes adversely affects income inequality, its economic benefits are debatable.

- Transfer Payments - Transfer payments refer to payments to persons such as social security, unemployment compensation, or welfare. CBO reported in November 2014 that: "Government transfers reduce income inequality because the transfers received by lower-income households are larger relative to their market income than are the transfers received by higher-income households. Federal taxes also reduce income inequality, because the taxes paid by higher-income households are larger relative to their before-tax income than are the taxes paid by lower-income households. The equalizing effects of government transfers were significantly larger than the equalizing effects of federal taxes from 1979 to 2011. CBO also reported that less progressive tax and transfer policies have contributed to greater after-tax income inequality: "As a result of the diminishing effect of transfers and federal taxes, the Gini index for income after transfers and federal taxes grew by more than the index for market income. Between 1979 and 2007, the Gini index for market income increased by 23 percent, the index for market income after transfers increased by 29 percent, and the index for income measured after transfers and federal taxes increased by 33 percent."

Other Causes:

- Decline of Unions - The era of inequality growth has coincided with a dramatic decline in labor union membership from 20% of the labor force in 1983 to about 12% in 2007.

- Political Parties and Presidents - Liberal political scientist Larry Bartels has found a strong correlation between the party of the president and income inequality in America since 1948. Examining average annual pre-tax income growth from 1948 to 2005 (which encompassed most of the egalitarian Great Compression and the entire inegalitarian Great Divergence) Bartels shows that under Democratic presidents (from Harry Truman forward), the greatest income gains have been at the bottom of the income scale and tapered off as income rose. Under Republican presidents, in contrast, gains were much less but what growth there was concentrated towards the top, tapering off as you went down the income scale.

- Non-Party Political Action - According to political scientists Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson writing in the book Winner-Take-All Politics, the important policy shifts were brought on not by the Republican Party but by the development of a modern, efficient political system, especially lobbying, by top earners – and particularly corporate executives and the financial services industry. Change in the norms of corporate culture also may have played a factor.

- Immigration - The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 increased immigration to America, especially of non-Europeans. From 1970 to 2007, the foreign-born proportion of America's population grew from 5% to 11%, most of whom had lower education levels and incomes than native-born Americans. But the contribution of this increase in supply of low-skill labor seem to have been relatively modest. One estimate stated that immigration reduced the average annual income of native-born "high-school dropouts" ("who roughly correspond to the poorest tenth of the workforce") by 7.4% from 1980 to 2000. The decline in income of better educated workers was much less. Author Timothy Noah estimates that "immigration" is responsible for just 5% of the "Great Divergence" in income distribution, as does economist David Card. While immigration was found to have slightly depressed the wages of the least skilled and least educated American workers, it doesn't explain rising inequality among high school and college graduates.

- Wage Theft - Wage theft in the United States, is the illegal withholding of wages or the denial of benefits that are rightfully owed to an employee. Wage theft can be conducted through various means such as: failure to pay overtime, minimum wage violations, employee misclassification, illegal deductions in pay, working off the clock, or not being paid at all. Wage theft, particularly from low wage legal or illegal immigrant workers, is common in the United States, according to some studies. A September 2014 report by the Economic Policy Institute suggests wage theft costs US workers billions of dollars a year and claims wage theft is also responsible for exacerbating income inequality.

- Corporatism - Edmund Phelps, published an analysis in 2010 theorizing that the cause of income inequality is not free market capitalism, but instead is the result of the rise of corporatism. Corporatism, in his view, is the antithesis of free market capitalism. It is characterized by semi-monopolistic organizations and banks, big employer confederations, often acting with complicit state institutions in ways that discourage (or block) the natural workings of a free economy. The primary effects of corporatism are the consolidation of economic power and wealth with end results being the attrition of entrepreneurial and free market dynamism

- Neoliberalism - Some economists, sociologists and anthropologists argue that neoliberalism, or the resurgence of 19th century theories relating to laissez-faire economic liberalism in the late 1970s, has been the significant driver of inequality. Vicenç Navarro points to policies pertaining to the deregulation of labor markets, privatization of public institutions, union busting and reduction of public social expenditures as contributors to this widening disparity. The privatization of public functions, for example, grows income inequality by depressing wages and eliminating benefits for middle class workers while increasing income for those at the top. The deregulation of the labor market undermined unions by allowing the real value of the minimum wage to plummet, resulting in employment insecurity and widening wage and income inequality. David M. Kotz, professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, contends that neoliberalism "is based on the thorough domination of labor by capital." As such, the advent of the neoliberal era has seen a sharp increase in income inequality through the decline of unionization, stagnant wages for workers and the rise of CEO super salaries.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Causes_of_income_inequality_in_the_United_States

If you thought income inequality was bad, get a load of wealth inequality

When we think about and discuss economic inequality in this country, we usually focus on income inequality: The CEO who makes 300 times more than his workers, or the fact that the top 20 percent of earners rake in over 50 percent of the total earnings in any given year.

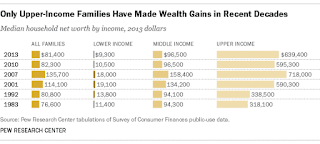

But there's another type of inequality that gets a lot less attention. It arguably contributes far more to the divide between the haves and have-nots in this country, and it's been highlighted in a huge new report from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development: wealth inequality.

Income is the amount of money you earn from your work or your investments. But wealth is the amount of stuff you own: your house, your car, savings, retirement accounts, etc. The great thing about wealth is that it's self-perpetuating. Your house gains value over time (so you hope). You can take $1,000, invest it in something that yields a 10 percent return, and have $1,100 by the year's end. Cool!

...

...

...

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/05/21/the-top-10-of-americans-own-76-of-the-stuff-and-its-dragging-our-economy-down/

The Many Ways to Measure Economic Inequality

September 22, 2015

The many ways to measure economic inequality

By Drew DeSilver

...

...

...

...

http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/09/22/the-many-ways-to-measure-economic-inequality/

35 soul-crushing facts about American income inequality.

Here are 35 soul-crushing facts about American income inequality. For example, the money given out in Wall Street bonuses last year was twice the amount all minimum-wage workers earned combined.

Inequality In U.S. Is Scarily High and Rising

In June 2013, President Obama acknowledged that inequality is on the rise "even though the economy is growing." That growth hasn't helped many people who lost mid-wage jobs during the recession. Half of the U.S. population is now considered poor or low-income, and income has been redistributed from the middle class to the very rich faster under Obama than under George W. Bush.

Income inequality in the U.S. is much worse than it is in other industrialized countries, where it is also an alarming problem, according to a new report from the International Labour Organization. The gap is only getting wider as the median wage continues to fall.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/06/12/inequality-us-_n_3421381.html

An OECD study in 2013 found that the U.S. had the highest income inequality in the developed world.

An OECD study in 2013 found that the U.S. had the highest income inequality in the developed world.

Read more here:

http://www.oecd.org/els/soc/OECD2013-Inequality-and-Poverty-8p.pdf

Read more here:

http://www.oecd.org/els/soc/OECD2013-Inequality-and-Poverty-8p.pdf

Next Time Someone Argues For 'Trickle-Down' Economics, Show Them This

In her Huffington Post article, Kathleen Miles suggests that the "Next Time Someone Argues For 'Trickle-Down' Economics, Show Them This."

February 6, 2014

Conservatives like to say that "a rising tide lifts all boats." In other words, if an executive makes $20 million a year, his income will eventually trickle down into the rest of the economy and ultimately benefit poor people.

But that theory hasn't exactly proven true. The highest-earning 20 percent of Americans have been making more and more over the past 40 years. Yet no other boats have risen; in fact, they're sinking. Over the same 40 years, the lowest-earning 60 percent of Americans have been making less and less.

Imagine the lines below as tides. As you can see, one is rising, while the others are falling (and one is stagnant):

The chart comes from the Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality's recently released 2014 report. The researchers looked at rising poverty and inequality in the U.S., particularly since the 2007-2008 recession.

Other studies have shown a correlation between bigger tax cuts for the 1 percent and income inequality. In the U.S., the top earners have made more money in the last 60 years as the top marginal tax rate has been slashed and as the rising dominance of Wall Street has allowed a few to make enormous profits.

An OECD study in 2013 found that the U.S. had the highest income inequality in the developed world. Out of all nations, only Chile, Mexico and Turkey had higher levels of income inequality, according to the study.

So what does this all mean in actual dollars? It means that more than half of U.S. wage earners made less than $30,000 in 2012, which is not far above the $27,010 federal poverty line for a family of five. Meanwhile, the top 10 percent of earners took more than half of the country's total income in 2012.

In other words, a rising tide has lifted a few big boats and washed the rest aside.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/02/06/rich-richer_n_4731408.html

February 6, 2014

Conservatives like to say that "a rising tide lifts all boats." In other words, if an executive makes $20 million a year, his income will eventually trickle down into the rest of the economy and ultimately benefit poor people.

But that theory hasn't exactly proven true. The highest-earning 20 percent of Americans have been making more and more over the past 40 years. Yet no other boats have risen; in fact, they're sinking. Over the same 40 years, the lowest-earning 60 percent of Americans have been making less and less.

Imagine the lines below as tides. As you can see, one is rising, while the others are falling (and one is stagnant):

The chart comes from the Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality's recently released 2014 report. The researchers looked at rising poverty and inequality in the U.S., particularly since the 2007-2008 recession.

Other studies have shown a correlation between bigger tax cuts for the 1 percent and income inequality. In the U.S., the top earners have made more money in the last 60 years as the top marginal tax rate has been slashed and as the rising dominance of Wall Street has allowed a few to make enormous profits.

An OECD study in 2013 found that the U.S. had the highest income inequality in the developed world. Out of all nations, only Chile, Mexico and Turkey had higher levels of income inequality, according to the study.

So what does this all mean in actual dollars? It means that more than half of U.S. wage earners made less than $30,000 in 2012, which is not far above the $27,010 federal poverty line for a family of five. Meanwhile, the top 10 percent of earners took more than half of the country's total income in 2012.

In other words, a rising tide has lifted a few big boats and washed the rest aside.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/02/06/rich-richer_n_4731408.html

The U.S. Is Even More Unequal Than You Realized

The chart above, from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) using the World Top Incomes Database, shows how income gains between 1975 and 2007 were divvied up in 18 OECD countries for which the researchers had data. Nowhere did the rich benefit as much as in America.

As you can see, in some countries like Denmark the vast majority of income gains went to the bottom 90 percent -- SOCIALISTS! -- while nearly half of U.S. income gains went to the richest one percent because freedom, baby.

America’s top 1 percent of earners accounted for 47 percent of all pre-tax income growth over that time period. And that’s excluding capital gains, for God's sake. Throw in the rest of the top 10 percent, and you’re looking at a group that got four-fifths of all income growth between the Ford and George W. Bush administrations. The rest of us were left to scramble for the last one-fifth of extra income. If you add in capital gains, which typically accrue to the highest earners anyway, the picture is probably a lot worse.

That trend had a big impact on total income share: Between 1981 and 2012, the top 1 percent more than doubled their share of total pre-tax income. They now account for about 20 percent of the nation's earnings. That's more than any other OECD country for which we have data:

But for truly shocking numbers, consider America’s even more-exclusive 0.1-percent club. Those super-duper-rich people -- we’re talking Warren Buffett rich -- saw their share of the income pot jump all the way to 8 percent in 2010 from just 2 percent in 1980. The super-duper rich swoop up smaller percentages in countries like Canada, the United Kingdom and Australia.

The super-rich getting super-richer would all be well and good, except that it doesn’t appear the nation’s “wealth creators” are creating much wealth for anyone else. According to the OECD’s report, the pre-tax, inflation-adjusted incomes of the bottom 99 percent have only grown by an average of 0.6 percent per year in recent decades. Add in the top one percent, and the country's income growth rate jumps to 1 percent.

This lack of trickle-down prosperity is a key focus of Capital in the Twenty-first Century, the new manifesto by French economist Thomas Piketty that destroys the argument for supply-side economics.

A common argument put forth by defenders of income inequality -- yes, they exist -- is that a rather large percentage of Americans move in and out of the 1 percent over the course of their lives, so the divide between the rich and everyone else is a bit of a false distinction in their view.

But while the country's economic mobility hasn’t gotten worse over the past few decades, it has essentially plateaued at a level lower than that of the Canadians. And I think we can all agree that if we have to deal with American levels of inequality, we can at least strive for Canadian levels of mobility.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/05/01/income-inequality-charts_n_5241586.html

The American Middle Class Is No Longer the World’s Richest

The American Middle Class Is No Longer the World’s Richest

By David Leonhardt and Kevin Quealy

April 22, 2014

The American middle class, long the most affluent in the world, has lost that distinction.

While the wealthiest Americans are outpacing many of their global peers, a New York Times analysis shows that across the lower- and middle-income tiers, citizens of other advanced countries have received considerably larger raises over the last three decades.

After-tax middle-class incomes in Canada — substantially behind in 2000 — now appear to be higher than in the United States. The poor in much of Europe earn more than poor Americans.

The numbers, based on surveys conducted over the past 35 years, offer some of the most detailed publicly available comparisons for different income groups in different countries over time. They suggest that most American families are paying a steep price for high and rising income inequality.

Although economic growth in the United States continues to be as strong as in many other countries, or stronger, a small percentage of American households is fully benefiting from it. Median income in Canada pulled into a tie with median United States income in 2010 and has most likely surpassed it since then. Median incomes in Western European countries still trail those in the United States, but the gap in several — including Britain, the Netherlands and Sweden — is much smaller than it was a decade ago.

In European countries hit hardest by recent financial crises, such as Greece and Portugal, incomes have of course fallen sharply in recent years.

The income data were compiled by LIS, a group that maintains the Luxembourg Income Study Database. The numbers were analyzed by researchers at LIS and by The Upshot, a New York Times website covering policy and politics, and reviewed by outside academic economists.

The struggles of the poor in the United States are even starker than those of the middle class. A family at the 20th percentile of the income distribution in this country makes significantly less money than a similar family in Canada, Sweden, Norway, Finland or the Netherlands. Thirty-five years ago, the reverse was true.

LIS counts after-tax cash income from salaries, interest and stock dividends, among other sources, as well as direct government benefits such as tax credits.

The findings are striking because the most commonly cited economic statistics — such as per capita gross domestic product — continue to show that the United States has maintained its lead as the world’s richest large country. But those numbers are averages, which do not capture the distribution of income. With a big share of recent income gains in this country flowing to a relatively small slice of high-earning households, most Americans are not keeping pace with their counterparts around the world.

“The idea that the median American has so much more income than the middle class in all other parts of the world is not true these days,” said Lawrence Katz, a Harvard economist who is not associated with LIS. “In 1960, we were massively richer than anyone else. In 1980, we were richer. In the 1990s, we were still richer.”

That is no longer the case, Professor Katz added.

Median per capita income was $18,700 in the United States in 2010 (which translates to about $75,000 for a family of four after taxes), up 20 percent since 1980 but virtually unchanged since 2000, after adjusting for inflation. The same measure, by comparison, rose about 20 percent in Britain between 2000 and 2010 and 14 percent in the Netherlands. Median income also rose 20 percent in Canada between 2000 and 2010, to the equivalent of $18,700.

The most recent year in the LIS analysis is 2010. But other income surveys, conducted by government agencies, suggest that since 2010 pay in Canada has risen faster than pay in the United States and is now most likely higher. Pay in several European countries has also risen faster since 2010 than it has in the United States.

Three broad factors appear to be driving much of the weak income performance in the United States. First, educational attainment in the United States has risen far more slowly than in much of the industrialized world over the last three decades, making it harder for the American economy to maintain its share of highly skilled, well-paying jobs.

Americans between the ages of 55 and 65 have literacy, numeracy and technology skills that are above average relative to 55- to 65-year-olds in rest of the industrialized world, according to a recent study by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, an international group. Younger Americans, though, are not keeping pace: Those between 16 and 24 rank near the bottom among rich countries, well behind their counterparts in Canada, Australia, Japan and Scandinavia and close to those in Italy and Spain.

A second factor is that companies in the United States economy distribute a smaller share of their bounty to the middle class and poor than similar companies elsewhere. Top executives make substantially more money in the United States than in other wealthy countries. The minimum wage is lower. Labor unions are weaker.

And because the total bounty produced by the American economy has not been growing substantially faster here in recent decades than in Canada or Western Europe, most American workers are left receiving meager raises.

Finally, governments in Canada and Western Europe take more aggressive steps to raise the take-home pay of low- and middle-income households by redistributing income.

Janet Gornick, the director of LIS, noted that inequality in so-called market incomes — which does not count taxes or government benefits — “is high but not off the charts in the United States.” Yet the American rich pay lower taxes than the rich in many other places, and the United States does not redistribute as much income to the poor as other countries do. As a result, inequality in disposable income is sharply higher in the United States than elsewhere.

Whatever the causes, the stagnation of income has left many Americans dissatisfied with the state of the country. Only about 30 percent of people believe the country is headed in the right direction, polls show.

“Things are pretty flat,” said Kathy Washburn, 59, of Mount Vernon, Iowa, who earns $33,000 at an Ace Hardware store, where she has worked for 23 years. “You have mostly lower level and high and not a lot in between. People need to start in between to work their way up.”

Middle-class families in other countries are obviously not without worries — some common around the world and some specific to their countries. In many parts of Europe, as in the United States, parents of young children wonder how they will pay for college, and many believe their parents enjoyed more rapidly rising living standards than they do. In Canada, people complain about the costs of modern life, from college to monthly phone and Internet bills. Unemployment is a concern almost everywhere.

But both opinion surveys and interviews suggest that the public mood in Canada and Northern Europe is less sour than in the United States today.

“The crisis had no effect on our lives,” Jonas Frojelin, 37, a Swedish firefighter, said, referring to the global financial crisis that began in 2007. He lives with his wife, Malin, a nurse, in a seaside town a half-hour drive from Gothenburg, Sweden’s second-largest city.

They each have five weeks of vacation and comprehensive health benefits. They benefited from almost three years of paid leave, between them, after their children, now 3 and 6 years old, were born. Today, the children attend a subsidized child-care center that costs about 3 percent of the Frojelins’ income.

Even with a large welfare state in Sweden, per capita G.D.P. there has grown more quickly than in the United States over almost any extended recent period — a decade, 20 years, 30 years. Sharp increases in the number of college graduates in Sweden, allowing for the growth of high-skill jobs, has played an important role.

Elsewhere in Europe, economic growth has been slower in the last few years than in the United States, as the Continent has struggled to escape the financial crisis. But incomes for most families in Sweden and several other Northern European countries have still outpaced those in the United States, where much of the fruits of recent economic growth have flowed into corporate profits or top incomes.

This pattern suggests that future data gathered by LIS are likely to show similar trends to those through 2010.

There does not appear to be any other publicly available data that allows for the comparisons that the LIS data makes possible. But two other sources lead to broadly similar conclusions.

A Gallup survey conducted between 2006 and 2012 showed the United States and Canada with nearly identical per capita median income (and Scandinavia with higher income). And tax records collected by Thomas Piketty and other economists suggest that the United States no longer has the highest average income among the bottom 90 percent of earners.

One large European country where income has stagnated over the past 15 years is Germany, according to the LIS data. Policy makers in Germany have taken a series of steps to hold down the cost of exports, including restraining wage growth.

Even in Germany, though, the poor have fared better than in the United States, where per capita income has declined between 2000 and 2010 at the 40th percentile, as well as at the 30th, 20th, 10th and 5th.

Malin Frojelin lives with her two children, Engla, 6, and Nils, 3, in Vallda, Sweden, along with her husband, Jonas. Vallda is about a 30-minute drive from Gothenburg, the…second-largest city in the country.

More broadly, the poor in the United States have trailed their counterparts in at least a few other countries since the early 1980s. With slow income growth since then, the American poor now clearly trail the poor in several other rich countries. At the 20th percentile — where someone is making less than four-fifths of the population — income in both the Netherlands and Canada was 15 percent higher than income in the United States in 2010.

By contrast, Americans at the 95th percentile of the distribution — with $58,600 in after-tax per capita income, not including capital gains — still make 20 percent more than their counterparts in Canada, 26 percent more than those in Britain and 50 percent more than those in the Netherlands. For these well-off families, the United States still has easily the world’s most prosperous major economy.

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/23/upshot/the-american-middle-class-is-no-longer-the-worlds-richest.html?_r=2

The Rising Costs of U.S. Income Inequality

In her December 1, 2014 article, Laura Tyson, the form chair of the U.S. President's Council of Economic Advisers, explains "The Rising Costs of U.S. Income Inequality."

BERKELEY, Calif. - During the last several decades, income inequality in the United States has increased significantly -- and the trend shows no sign of reversing. The last time inequality was as high as it is now was just before the Great Depression. Such a high level of inequality is not only incompatible with widely held norms of social justice and equality of opportunity; it poses a serious threat to America's economy and democracy.

Underlying the country's soaring inequality is income stagnation for the majority of Americans. With an expanding share of the gains from economic growth flowing to a tiny fraction of high-income U.S. households, average family income for the bottom 90 percent has been flat since 1980.

According to a recent report by the Council of Economic Advisers, if the share of income going to the bottom 90 percent was the same in 2013 as it was in 1973, median annual household income (adjusted for family size) would be 18 percent, or about $9,000, higher than it is now.

The disposable (after tax and transfer) incomes of poor families in the U.S. have trailed those of their counterparts in other developed countries for decades. Now the U.S. middle class is also falling behind.

During the last three decades, middle-income households in most developed countries enjoyed larger increases in disposable income than comparable U.S. households. This year, the U.S. lost the distinction of having the "most affluent" middle class to Canada, with several European countries not far behind. Once the generous public benefits in education, health care, and retirement are added to estimates of disposable family income in these countries, the relative position of the U.S. middle class slips even further.

The main culprit behind the languishing fortunes of America's middle class is slow wage growth. After peaking in the early 1970s, real (inflation-adjusted) median earnings of full-time workers aged 25-64 stagnated, partly owing to a slowdown in productivity growth and partly because of a yawning gap between productivity and wage growth.

Since 1980, average real hourly compensation has increased at an annual rate of 1 percent, or half the rate of productivity growth. Wage gains have also become considerably more unequal, with the biggest increases claimed by the top 10 percent of earners.

Moreover, technological change and globalization have reduced the share of middle-skill jobs in overall employment, while the share of lower-skill jobs has increased. These trends, along with a falling labor force participation rate during the last decade, explain the stagnation of middle class incomes.

For most Americans, wages are the primary source of disposable income, which in turn drives personal consumption spending -- by far the largest component of aggregate demand. Over the past several decades, as growth in disposable income slowed, middle and lower income households turned to debt to sustain consumption.

Personal savings rates collapsed, and credit and mortgage debt soared, as households attempted to keep pace with the consumption norms of the wealthy. For quite some time, growing income inequality did not slow consumption growth; indeed, "trickle-down consumption" pressures fostered more consumer spending, more debt, more bankruptcy and more financial stress among middle and lower income households.

The moment of reckoning arrived with the 2007-2008 financial crisis. Since then, aggregate consumption growth has been lackluster, as middle- and lower-income families have been forced to reduce their borrowing and pay down their debt, often through painful defaults on their homes -- their primary (and often their only) asset.

As these families have tightened their belts, the pace of consumption spending and economic growth has become more dependent on earners at the top of the income distribution. Since the recession ended in 2009, real consumption spending by the top 5 percent has increased by 17 percent, compared to just 1 percent for the bottom 95 percent.

The recovery's pattern has reinforced longer-run trends. In 2012, the top 5 percent of earners accounted for 38 percent of personal-consumption expenditure, compared to 27 percent in 1995. During that period, the consumption share for the bottom 80 percent of earners dropped from 47 percent to 39 percent.

Looking to the future, growing income inequality and stagnant incomes for the majority of Americans mean weaker aggregate demand and slower growth. Even more important, income inequality constrains economic growth on the supply side through its adverse effects on educational opportunity and human capital development.

Children born into low and high income families are born with similar abilities. But they have very different educational opportunities, with children in low income families less likely to have access to early childhood education, more likely to attend under-resourced schools that deliver inferior K-12 education, and less likely to attend or complete college.

The resulting educational attainment gap between children born into low and high-income families emerges at an early age and grows over time. By some estimates, the gap today is twice as large as it was two decades ago. So the U.S. is caught in a vicious circle: rising income inequality breeds more inequality in educational opportunity, which generates greater inequality in educational attainment. That, in turn, translates into a waste of human talent, a less educated workforce, slower economic growth, and even greater income inequality.

Although the economic costs of income inequality are substantial, the political costs may prove to be the most damaging and dangerous. The rich have both the incentives and the ability to promote policies that maintain or enhance their position.

Given the U.S. Supreme Court's evisceration of campaign finance restrictions, it has become easier than ever for concentrated economic power to exercise concentrated political power. Though campaign contributions do not guarantee victory, they give the economic elite greater access to legislators, regulators, and other public officials, enabling them to shape the political debate in favor of their interests.

As a result, the U.S. political system is increasingly dominated by money. This is a clear sign that income inequality in the U.S. has risen to levels that threaten not only the economy's growth, but also the health of its democracy.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/laura-tyson/us-income-inequality-costs_b_6249904.html

This piece also appeared on Project-Syndicate.org:

http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/cost-of-us-income-inequality-by-laura-tyson-2014-11

Voting to Cut Taxes Might Actually Increase Your Taxes - Evidence from Florida

Amendment One to the Constitution of the State of Florida promised to provide residents with property tax relief. But a primary consequence has been to shift the overall tax burden from the wealthy to everyone else.

http://econperspectives.blogspot.com/search/label/Florida%20amendment%20one

As the sociologists Stephen McNamee and Robert Miller Jr. point out in their book, The Meritocracy Myth, Americans widely believe that success is due to individual talent and effort. The book challenges that widely held American belief in meritocracy - that people get out of the system what they put into it based on individual merit.

http://www.amazon.com/Meritocracy-Myth-Stephen-J-McNamee/dp/0742561682/

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)